Bread of the Poilu, Part I: The Bread Ration

|

| Poilu |

I apologize for not responding yet to the many comments, and will answer them as quickly as possible.

For those unfamiliar with the term, "poilu" (translation, "hairy one") was a slang term applied to French infantrymen of World War I, a reference to their unshaven (and often unkempt) appearance which was also considered to be rather manly and virile.

But on to the bread: in the French army of World War I, as with most European armies of the time, bread was a critical part of the soldier’s daily rations whether in garrison or in the field. This is shown in the chart below. The daily bread ration of the French soldier throughout both world wars was 750 grams (~26.5 ounces).

Daily Bread Ration, 1914

| ||||

Country

|

Bread

|

Hard Bread

| ||

metric

|

US/English

|

metric

|

US/English

| |

Austria-Hungary

|

700 or 840 grams*

|

24.5 or 29.5 ounces*

|

500 grams

|

17.5 ounces

|

France

|

750 grams

|

26.5 ounces

|

600 grams

|

21 ounces

|

Germany**

|

750 grams

|

26.5 ounces

|

500 grams

|

17.5 ounces

|

Great Britain

|

450 or 570 grams*

|

16 or 20 ounces*

|

450 grams

|

16 ounces

|

Italy**

|

700 grams

|

24.5 ounces

| ||

Russia

|

1024 grams***

|

36 ounces

|

717 grams

|

25.5 ounces

|

*Rations amounts varied, dependent on a number of factors such as type of unit and proximity to the front lines.

**Same bread ration weight in WWII

|

***Originally measured in the Tsarist-era system of measures. The wartime bread ration was

2.5 "funt" (фунт). One funt=approx. 409.5 grams

|

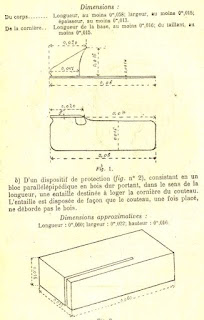

In the French Army, fresh bread was commonly in the form of pain ordinaire, literally “ordinary bread”, but perhaps more aptly translated as “standard bread”. Pain ordinaire was produced in round loaves of 1500 grams in weight: two daily rations. It was a round, flattened loaf approximately 270 mm in diameter and 97 mm in height (approx. 10.5 x 4 inches). It had a somewhat tough crust, a dense crumb and fairly low moisture content which allowed it to remain edible (after 18 hours of "ressuage", or resting after baking to allow for venting of excess moisture) for up to five or six days in summer or eight days in winter, and to stand up to rough handling while in transport.

|

|

French soldiers carrying their dinner, soup and bread, 1915.

The bread is pain ordinaire or pain biscuité.

gallica.bnf.fr / Biblioteque nationale de France

|

|

| At Amiens (Somme) a pile of pain ordinaire on the ground, awaiting transport. |

Pain biscuité (biscuit bread) was pain ordinaire prepared

in a slightly different manner and baked longer to produce bread with lower

moisture content in order to increase its keeping qualities to 20-25 days. Of

approximately the same size and shape as pain ordinaire, pain biscuité had a

slightly flatter shape, a thicker crust and weighed 1400 grams (~50 ounces) due to its

lower moisture content. The daily bread ration for pain biscuité was 700

grams. As it was less susceptible to mold, pain

biscuité made with brewer’s yeast and cooled for 24 hours could be stored

for as long as 18 to 20 days, but was recommended to be used by the 10th

day.

|

| Arrival of bread and tobacco rations by truck. |

A third type of bread was the French WWI version of hardtack, "pain de guerre" (war bread). It was a departure from the traditional type of hard bread or hard tack in that pain de guerre included leavening. While it didn't have the long-time storage capability of previous hard breads, it was more palatable and less likely to cause digestive problems.

There were many sources for bread in the French Army. Bread could be procured from civilian bakeries in time of extreme need, but was more commonly produced in permanent army bakeries, field ovens or in rolling ovens (“boulangeries roulantes”) that accompanied units in the field.

Even while moving daily and under adverse conditions, field bakeries equipped with boulangeries roulantes were expected to be able to produce an output of not less than six batches of bread in twenty-four hours, The production of a bakery unit of 32 boulangeries roulantes was rated at 26,880 rations (13,440 loaves) per day.

|

| (above and below) Testing field ovens (boulangeries roulantes), Argenteuil (suburb of Paris), 6 May, 1914. |

Coming soon, how to make your own pain ordinaire (see photos below).

I need to tweak the formula just one more time before unleashing it.

Sources

L'Intendance

en Campagne,

enri

Charles-Lavauzelle, Éditeur militaire (Military publisher), Paris, 1914

No. 96bis,

Instruction sur les Boulangeries Légères de Campagne

Henri

Charles-Lavauzelle, Éditeur militaire (Military publisher), Paris, 1901

No. 96,

Subsistances Militaires, Boulangeries Roulantes de Campagne

Henri

Charles-Lavauzelle, Éditeur militaire (Military publisher), Paris, 1910

No. 96,

Subsistances Militaires, Boulangeries Roulantes de Campagne

Henri

Charles-Lavauzelle, Éditeur militaire (Military publisher), Paris, 1915